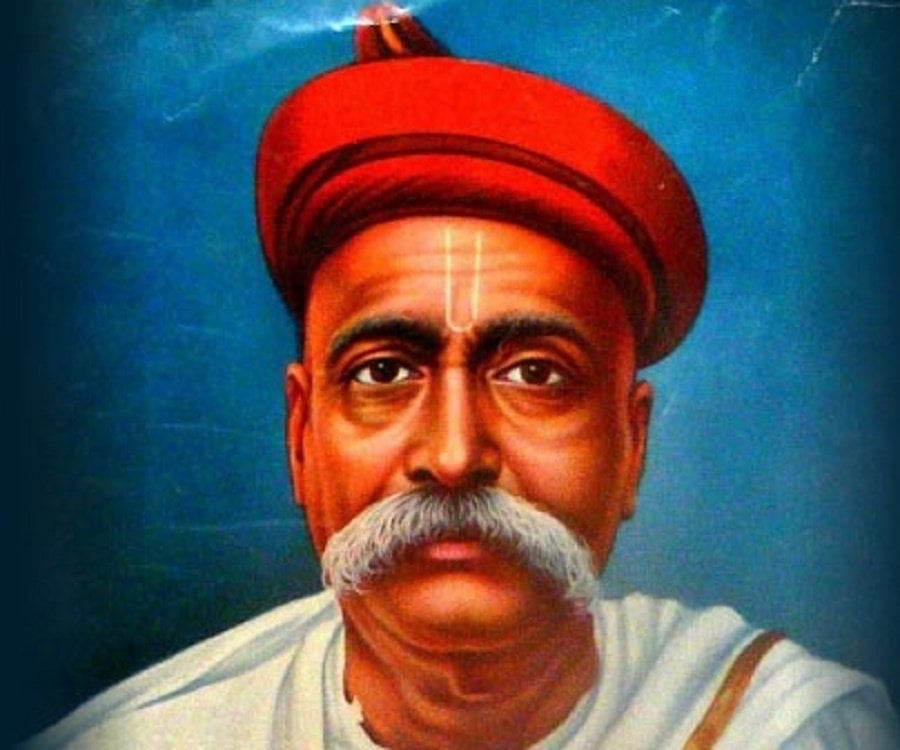

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, also known as Lokmanya, was a prominent figure in India's independence movement. He was born on July 23, 1856 and is remembered as a nationalist, teacher, and independence activist. Tilak was part of the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate and was referred to as "The father of the Indian unrest" by the British colonial authorities. However, he was also respected by his fellow Indians and was given the title of "Lokmanya", meaning "accepted by the people as their leader." Mahatma Gandhi even referred to him as "The Maker of Modern India."

Tilak was a strong advocate for self-rule, or Swaraj, and was a radical voice in the Indian consciousness. He famously said, "Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it!" Tilak formed close alliances with many other leaders in the Indian National Congress, including Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Aurobindo Ghose, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Early Life

Keshav Gangadhar Tilak, who would later be known as Bal Gangadhar Tilak or Lokmanya, was born into a Marathi Hindu Chitpavan Brahmin family in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra on July 23, 1856. His father, Gangadhar Tilak, was a school teacher and Sanskrit scholar. Tilak received his Bachelor of Arts in Mathematics from Deccan College in Pune in 1877 and later obtained his L.L.B degree from Government Law College in 1879.

After graduation, Tilak began teaching mathematics at a private school in Pune. However, he eventually left teaching and became a journalist due to ideological differences with his colleagues. Tilak was actively involved in public affairs and believed that religion and practical life were interconnected. He believed in serving others and making the country one's family, as well as serving humanity and God.

Tilak was deeply committed to the cause of India's independence and was a key figure in the independence movement. He is remembered as "The father of the Indian unrest" by the British colonial authorities, but was also respected by his fellow Indians and given the title of "Lokmanya," meaning "accepted by the people as their leader." Mahatma Gandhi even referred to him as "The Maker of Modern India."

Inspired by Vishnushastri Chiplunkar, Bal Gangadhar Tilak co-founded the New English school in 1880 with a group of his college friends. Their aim was to improve the quality of education for India's youth and the success of the school led them to establish the Deccan Education Society in 1884. The Society's goal was to create a new system of education that taught young Indians nationalist ideas through a focus on Indian culture. As a result, the Society established Fergusson College in 1885 for post-secondary studies, where Tilak taught mathematics.

However, in 1890, Tilak left the Deccan Education Society to pursue more overtly political work. He began a mass movement towards independence, focusing on a religious and cultural revival. Tilak's efforts to inspire a sense of national pride and unity were instrumental in the independence movement and he is remembered as a key figure in India's fight for freedom.

Political Career

Throughout his political career, Bal Gangadhar Tilak fought for Indian autonomy from British colonial rule. He was a well-known political leader and, before Gandhi, was one of the most widely recognized figures in India's independence movement. While he was considered a radical nationalist, Tilak was also a social conservative.

Tilak was imprisoned multiple times, including a lengthy stint at Mandalay. He was even referred to as "the father of Indian unrest" by British author Sir Valentine Chirol due to his strong stance against colonial rule. Tilak's commitment to the cause of independence and his willingness to stand up against British authority earned him the respect and admiration of his fellow Indians. He is remembered as a key figure in the fight for freedom and is still honored and respected in India today.

Indian National Congress

Bal Gangadhar Tilak joined the Indian National Congress in 1890 and opposed its moderate approach, particularly when it came to the fight for self-government. He was a prominent radical figure at the time and played a key role in the Swadeshi movement of 1905-1907, which resulted in a split within the Indian National Congress into the Moderates and the Extremists.

In late 1896, a bubonic plague outbreak spread from Bombay to Pune and reached epidemic proportions by January 1897. The British Indian Army was called in to deal with the crisis and implemented strict measures to curb the spread of the disease, including forced entry into private homes, examination and evacuation of residents, and destruction of personal possessions. These measures caused widespread resentment among the Indian public.

Tilak took up this issue in his newspaper, Kesari, and published inflammatory articles quoting the Bhagavad Gita to argue that there was no blame for those who killed oppressors without reward. As a result, on June 22, 1897, Commissioner Rand and another British officer were killed by the Chapekar brothers and their associates. It is believed that Tilak may have concealed the identities of the perpetrators. He was charged with incitement to murder and sentenced to 18 months in prison. Upon his release, Tilak was revered as a martyr and national hero and adopted the slogan "Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it." His dedication to the cause of independence and willingness to stand up against British rule earned him the respect and admiration of his fellow Indians.

After the Partition of Bengal, which was a strategy implemented by Lord Curzon to weaken the independence movement in India, Bal Gangadhar Tilak encouraged the Swadeshi and Boycott movements. The Boycott movement called for the boycott of foreign goods and the social boycott of any Indian who used foreign products. The Swadeshi movement promoted the use of natively produced goods. The goal of these movements was to fill the gap left by the boycott of foreign goods with the production of those goods in India itself. Tilak believed that the Swadeshi and Boycott movements were interconnected and necessary for the success of the independence movement.

Tilak's support for these movements helped to strengthen the fight for independence and his dedication to the cause earned him the respect and admiration of his fellow Indians. He is remembered as a key figure in the fight for freedom and is still honored and respected in India today.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak opposed the moderate views of Gopal Krishna Gokhale and was supported by Bipin Chandra Pal in Bengal and Lala Lajpat Rai in Punjab, who were known as the "Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate." In 1907, the annual Congress Party session was held in Surat, Gujarat and tensions arose over the selection of the new party president between the moderate and radical factions. As a result, the party split into the radical faction, led by Tilak, Pal, and Lajpat Rai, and the moderate faction. Nationalists such as Aurobindo Ghose and V. O. Chidambaram Pillai were supporters of Tilak and the radical faction.

Tilak's commitment to the independence movement and his strong stance against colonial rule made him a respected and influential figure in India. He is remembered as a key figure in the fight for freedom and is still honored and respected in India today.

When asked about his vision for an independent India, Bal Gangadhar Tilak rejected the idea of a Maratha-dominated government, citing that the Maratha-dominated governments of the 17th and 18th centuries were outmoded in the 20th century. Instead, he advocated for a genuine federal system in which all citizens were equal partners. Tilak believed that this type of government would be best equipped to protect India's freedom. He was also the first Congress leader to suggest that Hindi written in the Devanagari script should be accepted as the national language of India.

Tilak's vision for an independent India was rooted in the belief that all citizens should be treated equally and that a strong and united nation was necessary to protect freedom. His commitment to these ideals earned him the respect and admiration of his fellow Indians and he is remembered as a key figure in the fight for independence.

Sedition Charges

During his lifetime, Bal Gangadhar Tilak faced sedition charges from the British Indian government on three occasions. In 1897, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison for inciting disaffection against British rule. In 1909, he was charged with sedition and intensifying racial animosity between Indians and the British and was sentenced to six years in prison in Burma. However, in 1916, Tilak was charged with sedition again, this time over his lectures on self-rule. Bombay lawyer Muhammad Ali Jinnah appeared as his defense lawyer and successfully led Tilak to acquittal.

Tilak's commitment to the cause of independence and his willingness to stand up against British rule earned him the respect and admiration of his fellow Indians. He is remembered as a key figure in the fight for freedom and is still honored and respected in India today.

Imprisonment in Mandalay

On April 30, 1908, two Bengali youths, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose threw a bomb at a carriage in an attempt to kill Chief Presidency Magistrate Douglas Kingsford of Calcutta, but mistakenly killed two women traveling in it. While Chaki committed suicide after being caught, Bose was hanged. Bal Gangadhar Tilak defended the revolutionaries in his newspaper, Kesari, and called for immediate self-rule, or Swaraj. The government quickly charged him with sedition and, after a trial, a special jury convicted him by a 7:2 majority. Judge Dinshaw D. Davar sentenced Tilak to six years in prison in Mandalay, Burma, and imposed a fine of ₹1,000 (US$13). When asked by the judge if he had anything to say, Tilak famously replied:

Muhammad Ali Jinnah acted as Tilak's lawyer in the case and the judgment by Judge Davar faced criticism for its lack of impartiality and was seen as biased against Tilak. In his sentence, Judge Davar condemned Tilak's articles as "seething with sedition" and preaching violence and spoke of murders with approval. He stated that such journalism was a "curse" to the country. Tilak was imprisoned in Mandalay from 1908 to 1914 and continued to read and write while in prison, further developing his ideas on the Indian independence movement. He wrote the Gita Rahasya, which was widely sold and the proceeds were donated to the independence movement.

Tilak's imprisonment and dedication to the cause of independence earned him the respect and admiration of his fellow Indians and he is remembered as a key figure in the fight for freedom. His legacy is still honored and respected in India today.

Life after Mandalay

During his time in Mandalay prison, Tilak developed diabetes and the general ordeal of prison life had a mellowing effect on him upon his release in June 1914. However, when World War I broke out in August of that year, Tilak expressed his support for the war efforts and used his oratory skills to recruit new soldiers. He also welcomed The Indian Councils Act, commonly known as the Minto-Morley Reforms, which had been passed by the British Parliament in May 1909, stating that it was a marked increase of confidence between the rulers and the ruled. Tilak believed that acts of violence actually hindered, rather than hastened, the pace of political reforms. He was eager for reconciliation with the Indian National Congress and abandoned his demand for direct action, instead opting for agitations through "strictly constitutional means" - a line that had long been advocated by his rival Gokhale. In 1916, Tilak reunited with his fellow nationalists and rejoined the Indian National Congress during the Lucknow pact.

Tilak tried to convince Mohandas Gandhi to abandon the idea of total non-violence and instead strive for self-rule through all means. Though Gandhi did not fully agree with Tilak's methods to achieve self-rule and remained committed to his advocacy of satyagraha, he still recognized Tilak's contributions to the country and his courage of conviction. After Tilak lost a civil suit against Valentine Chirol and incurred financial loss, Gandhi even called upon Indians to contribute to the Tilak Purse Fund, which was established to defray the expenses incurred by Tilak.

All India Home Rule League

Tilak helped establish the All India Home Rule League in 1916-18, alongside G.S. Khaparde and Annie Besant. After years of trying to reunite the moderate and radical factions of the Indian independence movement, Tilak focused on the Home Rule League, which aimed for self-rule. He traveled to villages across the country to gain support from farmers and locals to join the movement for self-rule. Tilak was impressed by the Russian Revolution and expressed admiration for Vladimir Lenin. The league had 1400 members in April 1916 and by 1917, membership had grown to approximately 32,000. Tilak started the Home Rule League in Maharashtra, Central Provinces, and the Karnataka and Berar regions, while Besant's League was active in the rest of India.

Thoughts and views

Religio-Political Views

Throughout his life, Tilak strived to unite the Indian population for mass political action. To achieve this, he believed there needed to be a comprehensive justification for anti-British and pro-Hindu activism. To this end, he sought justification in the supposed original principles of the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita. He named this call to activism karma-yoga or the yoga of action. In his interpretation, the Bhagavad Gita reveals this principle in the conversation between Krishna and Arjuna, where Krishna exhorts Arjuna to fight his enemies (which in this case included many members of his family) because it is his duty. In Tilak's opinion, the Bhagavad Gita provided a strong justification for activism. However, this conflicted with the mainstream exegesis of the text at the time, which was dominated by renunciate views and the idea of acts purely for God. This was represented by the two mainstream views at the time by Ramanuja and Adi Shankara.

To find support for this philosophy, Tilak wrote his own interpretations of the relevant passages of the Gita and backed his views using Jnanadeva's commentary on the Gita, Ramanuja's critical commentary, and his own translation of the Gita. His main battle was against the renunciate views of the time, which conflicted with worldly activism. To fight this, he went to great lengths to reinterpret words such as karma, dharma, and yoga, as well as the concept of renunciation itself. Because he founded his rationalization on Hindu religious symbols and lines, he alienated many non-Hindus, such as the Muslims, who began to ally with the British for support.

Social views against women

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was known for his strong opposition to social reforms and women's rights. He strongly opposed the establishment of the first Native girl's High school in Pune in 1885 and its curriculum, using his newspapers as a platform to voice his views. Tilak was also opposed to intercaste marriages and was willing to sign a circular that increased the age of marriage for girls to sixteen and twenty for boys.

Tilak's views on women were particularly concerning. He approved of the court's decision in the case of Rukhmabai who was ordered to go and live with her husband or face six months of imprisonment. Tilak also blamed an eleven-year-old Phulamani Bai for dying while having sexual intercourse with her much older husband, calling her one of those "dangerous freaks of nature". He did not believe that Hindu women should receive a modern education and had a more conservative view of women's roles, believing that they should subordinate themselves to their husbands and children.

Tilak's views on social issues were not progressive. He refused to sign a petition for the abolition of untouchability in 1918, despite having spoken against it earlier in a meeting. This highlights his deeply ingrained conservative views on the role of women and societal reforms in India. Although he was a celebrated independence activist, Tilak's views on social issues were not in line with the liberal and progressive ideas that were emerging in India at the time.

Esteem for Swami Vivekananda

Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Swami Vivekananda had a strong admiration for each other's work and ideals. They first met by chance on a train in 1892 and Tilak had the privilege of hosting the great spiritual leader in his home. A witness to the meeting, Basukaka, reported that the two men reached an agreement to work towards nationalism in different areas of life. Tilak would focus on the political arena while Vivekananda would concentrate on the spiritual arena.

The death of Swami Vivekananda at a young age was a great loss for Tilak. In his newspaper, the Kesari, Tilak expressed his sadness and paid tribute to the great spiritual leader. He believed that Swami Vivekananda was a modern-day Shankaracharya, who showed the world the glory and greatness of Hinduism. Tilak recognized the important work that Swami Vivekananda had done in spreading the teachings of the Advaita philosophy and in raising the profile of Hinduism globally. He also acknowledged that much work still remained to be done in this area.

Tilak regarded Swami Vivekananda as a great loss for Hinduism and for the world. In his words, "We have lost our glory, our independence, everything." Despite his sadness, Tilak recognized the importance of continuing the work started by Swami Vivekananda, and dedicated himself to the cause of nationalism, working towards the independence of India. The mutual respect and esteem shared by Tilak and Swami Vivekananda serves as a testament to their commitment to the cause of nationalism and their love for their country.

Conflicts with Shahu over caste issues

Despite these conflicts, Tilak and Shahu had a mutual respect for each other's work. Tilak was known for his strong stance on social justice and equality, which often put him at odds with the traditional caste system prevalent in India. His support for the Brahmins and his opposition to Shahu's caste prejudice was seen as a brave stance by many, especially considering the power and influence that Shahu held.

The allegations against Shahu of sexual assault against Brahmin women added fuel to the fire, and Tilak's newspapers and the press in Kolhapur were quick to publicize these allegations. Tilak also suffered from the confiscation of his estate by Shahu, which further strained their relationship. However, Tilak remained steadfast in his beliefs and continued to fight for the rights of the marginalized communities in India.

Despite these conflicts, Tilak and Shahu remained respectful of each other's work and continued to advocate for their respective causes. Tilak's tireless efforts towards nationalism and social justice continue to inspire millions of Indians even today, and his legacy remains an important part of India's rich cultural heritage.

Social contributions

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, also known as Lokmanya, was not only an Indian nationalist, teacher and independence activist but also a social reformer who made significant contributions to Indian society. He co-founded two weekly newspapers, Kesari in Marathi and Mahratta in English, which helped awaken the Indian consciousness and became a daily publication that still continues to this day. Tilak was also recognized as the founder of the grand public event, Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav, which was a household worship of Ganesha transformed into a grand public celebration that lasted several days.

In 1895, Tilak founded the Shri Shivaji Fund Committee for the celebration of Shiv Jayanti, the birth anniversary of the Maratha Empire's founder Shivaji. This project had the objective of funding the reconstruction of Shivaji's tomb (Samadhi) at Raigad Fort and also served as a way to build national spirit among the people and oppose the colonial rule. However, these celebrations also contributed to religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims, as the festival organizers urged Hindus to protect cows and boycott the Muharram celebrations organized by Shi'a Muslims.

Tilak also co-founded the Deccan Education Society in the 1880s, which still runs institutions in Pune such as the Fergusson College. He was instrumental in starting the Swadeshi movement at the beginning of the 20th century, which became a part of the independence movement until India achieved independence in 1947. This movement continued to be part of Indian government policy until the 1990s, when the Congress government liberalized the economy.

Tilak was a true patriot who dedicated his life to the political and social emancipation of his motherland and its people. He once said, "I regard India as my Motherland and my Goddess, the people in India are my kith and kin, and loyal and steadfast work for their political and social emancipation is my highest religion and duty". His social contributions continue to inspire future generations and his legacy remains an integral part of Indian history.

Books

In addition to his activism and political contributions, Tilak was also an accomplished author. He wrote several books on Indian history and culture, including The Arctic Home in the Vedas and Shrimadh Bhagvad Gita Rahasya. In The Arctic Home in the Vedas, Tilak presented his argument that the Vedas could only have been composed in the Arctic region and were brought south after the onset of the last ice age. He proposed a new way to determine the exact time of the Vedas by using the position of different Nakshatras.

Tilak's analysis of Karma Yoga in the Bhagavad Gita, written in prison at Mandalay, was also well-received. He wrote Shrimadh Bhagvad Gita Rahasya, which is considered to be a gift of the Vedas and the Upanishads. These books showcase Tilak's deep understanding of Hindu history and religion, and his efforts to educate the people about their cultural heritage.

Tilak's contributions to Indian literature and culture have made him a renowned figure in Indian history. His works have continued to inspire generations of Indians, and his legacy as an author and intellectual remains alive to this day.

Descendants

Tilak’s legacy continues to live on through his descendants. His son, Shridhar Tilak, was an advocate of the removal of untouchability in the late 1920s and worked alongside dalit leader, Dr. Ambedkar. Both were leaders of the multi-caste Samata sangh. Shridhar’s son, Jayantrao Tilak, was a well-known politician from the Congress party and served as a member of the Parliament of India representing Maharashtra in the Rajya Sabha. He was also the editor of the Kesari newspaper for many years.

Another descendant of Tilak, Rohit Tilak, is a politician from the Congress party based in Pune. However, in 2017, he was accused of rape and other crimes by a woman with whom he had an extramarital affair. Currently, he is out on bail in connection with these charges. Despite these allegations, Tilak’s legacy as a pioneering leader in the Indian independence movement continues to inspire generations. He will always be remembered as the “Maker of Modern India” and his ideals will continue to guide future leaders in their quest for a better, more just India.

Legacy

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, also known as Lokmanya, was a prominent figure in the Indian independence movement and an influential leader in the fight for self-rule. His contribution to the Indian independence movement was acknowledged when a portrait of him was placed in the Central Hall of Parliament House in 1956. The portrait, painted by Gopal Deuskar, was unveiled by the then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Tilak is also remembered through various memorials dedicated to him. The Tilak Smarak Ranga Mandir in Pune is a theater auditorium in his honor, and in 2007, the government of India released a coin to commemorate his 150th birth anniversary. In addition, a clafs-cum-lecture hall was built in Mandalay prison as a memorial to Lokmanya Tilak. The government of India provided ₹35,000 (US$440) for the construction, and the local Indian community in Burma added ₹7,500 (US$94) to the cause.

Tilak's life and legacy have also been portrayed in various Indian films, including the documentary films Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1951) and Lokmanya Tilak (1957), as well as the feature film Lokmanya: Ek Yugpurush (2015) and The Great Freedom Fighter Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak - Swaraj My Birthright (2018). These films aim to showcase Tilak's contributions to the Indian independence movement and to keep his memory alive for future generations.

Note

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, an influential figure in Indian politics, wrote about the need for a united front among the Chitpavans, Deshasthas, and Karhades in the late 19th century. He believed that these groups of Brahmans should give up their caste exclusiveness by encouraging inter-sub-caste marriages and community dining. Tilak had a great deal of respect and admiration for Swami Vivekananda and they had a mutual understanding that Tilak would work for nationalism in the political field while Vivekananda would work for nationalism in the religious field. Tilak was a great scholar and a fearless patriot who advocated for passive resistance and boycott of British goods. He was influenced by Vivekananda's dynamic personality and powerful exposition of the Vedantic doctrine. According to Tilak, Vivekananda had taken the responsibility of keeping the banner of Advaita philosophy flying among all the nations of the world and made people realize the true greatness of Hindu religion and Hindu people.

In the dispute over the Vedokta, Tilak and the anti-durbar press in Kolhapur aligned themselves with the Brahmins and reproved the Maharaja for his caste prejudice and unreasoned hostility towards Brahmins. However, the Bombay government and the Vicereine saw the Brahmins in Kolhapur as victims of persecution by the Maharaja. Natu and Tilak suffered from the durbar's confiscation of estates, and in 1906, the "poor helpless women" of Kolhapur petitioned Lady Minto alleging that the Maharaja had forcibly seduced Brahmin ladies and that the Political Agent had refused to act in the matter. The agent, however, blamed everything on the troublesome Brahmins.

FAQ

How did Bal Gangadhar Tilak become important?

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was an Indian nationalist and social reformer who played a significant role in the Indian independence movement. He became important for his contribution to the Indian National Congress and his advocacy of Indian self-rule.

Tilak was born on July 23, 1856, in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, India. He received his education at Deccan College in Pune and later obtained a law degree from the University of Bombay. Tilak began his career as a journalist and soon became a prominent writer and social reformer.

In 1890, Tilak founded the Kesari newspaper, which became a platform for his nationalist and social reform ideas. He also established the Deccan Education Society to promote education in India. In 1893, Tilak was elected to the Indian National Congress and became one of its most vocal and influential members.

Tilak was a strong advocate for Swaraj, or self-rule, for India. He believed that India could achieve independence through peaceful means and worked to mobilize public opinion in support of this goal. He was also a vocal critic of British colonialism and the economic exploitation of India.

Tilak's contribution to the Indian independence movement was significant. He organized several mass protests and movements, including the Swadeshi Movement, which called for the boycott of British goods and the promotion of Indian-made products. Tilak was also involved in the Non-Cooperation Movement, which aimed to achieve independence through non-violent means.

In 1916, Tilak helped negotiate the Lucknow Pact, which united the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League in a common struggle for self-rule. However, Tilak's radicalism and his advocacy of civil disobedience led to his imprisonment several times by the British authorities.

Despite his imprisonment and persecution, Tilak remained committed to the cause of Indian independence until his death in 1920. His legacy as a nationalist leader and social reformer continues to inspire Indians to this day.

How was Bal Gangadhar Tilak educated?

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was educated in Pune, Maharashtra, India. He attended primary school at a local village and then moved to Pune, where he studied at the Anglo-Vernacular School. After completing his primary education, Tilak attended the Deccan College in Pune, where he earned a bachelor's degree in Arts in 1877.

Tilak went on to study law at the Government Law College in Mumbai, and he graduated in 1880. During his time in Mumbai, Tilak was influenced by the ideas of Swami Dayananda Saraswati, the founder of the Arya Samaj movement, which advocated a return to Vedic principles and Hindu reform.

Tilak continued his education by studying Sanskrit and Marathi literature, which helped him to become a prominent writer and intellectual. He used his education and knowledge to promote social reform and nationalist ideas through his writings and speeches.

In addition to his formal education, Tilak was also self-taught and well-read. He was particularly interested in Indian history and culture, and he drew upon these subjects in his political writings and speeches. Tilak's education played a crucial role in shaping his ideas and philosophy, and he used his knowledge and expertise to become one of the most important figures in the Indian independence movement.

What is bal gangadhar tilak date of birth?

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was born on July 23, 1856.

Who was lokmanya tilak?

Lokmanya Tilak, also known as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, was an Indian nationalist, social reformer, and freedom fighter who played a pivotal role in India's struggle for independence from British rule. He was born on July 23, 1856, in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, India.

Tilak was a prominent member of the Indian National Congress and is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern India. He was a strong advocate for Swaraj, or self-rule, for India, and worked tirelessly to mobilize public opinion in support of this goal.

Tilak was also a champion of Hindu nationalism and the revival of Hindu culture and traditions. He founded the Ganapati festival, which is still celebrated throughout India as a symbol of Hindu unity and pride.

Tilak's contribution to the Indian independence movement was significant. He organized several mass protests and movements, including the Swadeshi Movement and the Non-Cooperation Movement, which aimed to achieve independence through non-violent means.

Despite his imprisonment and persecution by the British authorities, Tilak remained committed to the cause of Indian independence until his death in 1920. His legacy as a nationalist leader and social reformer continues to inspire Indians to this day, and he is remembered as one of India's most important and influential figures.